Over the Summer, I paid a visit to the Ironbridge Gorge in Shopshire, UK. Given ‘World Heritage’ status in 1986, Ironbridge Gorge is not the first place to smelt iron using a blast furnace, but it is the first place in which iron production through using a blast furnace, fuelled by coke rather than charcoal was carried out on an industrial scale. Within the slightly western-centric world of UNESCO (and Anglo-centric world of such industrial heritage sites in the UK), therefore, this is the “Birthplace of the Industrial Revolution”. In proclaiming that it was here where the industrial revolution was, quite literally, forged, one could also argue that it is here that the heritage of the anthropogenic capacity to effect climate is celebrated. This is perhaps one of the world’s key sites in the heritage of Anthropogenic climate change!

Comprising 11 museums, you can visit the first industrial scale forge from the 17th century, as well as the site where Abraham Darby expanded the scale of the forge in the 1770s in order to make the iconic ‘Iron Bridge’.

This is the world’s first structure that was built entirely of iron: the direct grandparent of every bridge, skyscraper, container ship and apartment block today. This is the heritage of the modern world system.

It is certainly a fascinating place, and it is interesting also in the manner in which the whole venture took place: amid a strange mix of making things up in the present in the context of extreme self-confidence, together with a sort of knowing ‘bravura’ about the future. In the 1770s, people did not know how to build an ‘iron bridge’, and so essentially they built a ‘wooden bridge’ out of iron: there are no rivets, and no soldering or welding. Instead, the whole structure is constructed using mortise and other timber joints. It was also constructed with an eye to contemporary marketing in mind: a hotel was built, with a direct view along the bridge, before the bridge was even completed because the builders were sure that this piece of industrial technology would be a tourist attraction right from the start. People like Abraham Darby wanted to show the world what amazing technologies and transformations that human ingenuity and endeavour could achieve; as if to say “LOOK! We humans can master the world around us; we humans can transform the landscape and the environment to our will”.

Ironbridge Gorge is a total landscape of industrial technology, and tourists have been visiting the site and have been amazed for more than 300 years. And I don’t suppose the irony would be lost to add that recent flooding and land movements have started to threaten the integrity of the entire valley. The iron bridge itself now has a measurably larger ‘summit’ on it than it had just 40 or 50 years ago, and millions of pounds are being spent to shore up the slopes, and to keep the valley ‘beautiful and maintain the site’s stability.

These efforts have been expended to maintain stability – to keep the bridge, the valley and the buildings in a sort of suspended animation of ‘total preservation’. This ambition is, of course, impossible, and is partly made impossible through the very activities that are being celebrated at the site.

These remains of a blast furnace at Blist’s Hill have apparently been voted as the world’s most “Alarmed-Looking Buildings” – very aposite for such a site of climate change heritage.

What is inscribed on World Heritage Site lists as a key site in the ‘heritage of modernity’, can be read as a site of the heritage of Anthropogenic climate change: a site that celebrates the moment at which human beings begin to transform the world and its climate in irreversible ways. This is a key site in the modern world system – a ‘heritage of the now’!

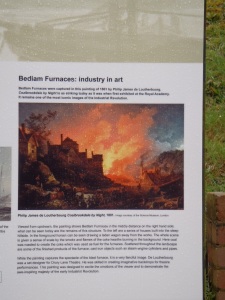

The river valley looks serene today, but of course a visitor in the 18th or 19th century would have witnessed a site of industrial devastation, shock, and awe. You can get a glimpse of this in de Loutherbourg’s famous painting from 1801 Coalbrookdale by Night (now held by the Science Museum in London), which is often seen to symbolise the birth of the Industrial Revolution. It depicts the Madeley Hill furnace, also known as the Bedlam Furnace – a knowing depiction of Chaos, and madness.

This is a World Heritage Site dedicated to celebrating the capacity for humans to alter the climate; perhaps a World Heritage Site dedicated to the birth of the so-called Anthropocene? As a viewer, of the valley and of this painting, we are both fascinated and appalled – it is ugly and irresistible; its internal logics talked about as ‘bedlam’ – as CHAOS.

This is a heritage of total transformation, and also one that prompts the sort of speculation into the future, that is at the heart of much climate change science; a recognition of total transformation in the present. This is an imagined transformation from a supposedly stable and harmonious past; mixed with anxiety about the future, and which fuels a whole industry of ‘speculation’ and concern: JUST HOW SCREWED-UP A WORLD, ARE WE GOING TO MAKE?!